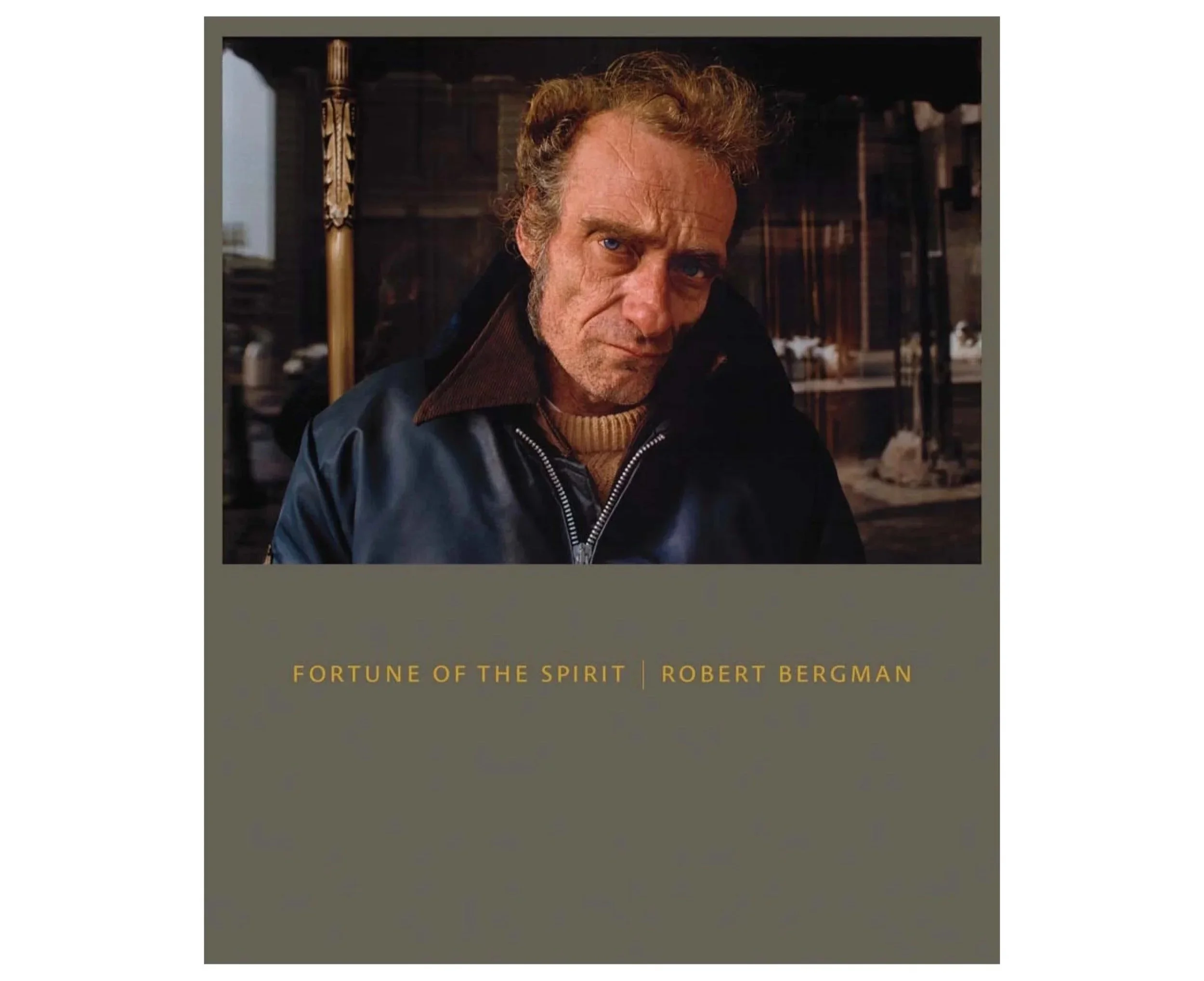

A couple of months ago, I stumbled across Fortune of the Spirit, a book of portraits taken by Robert Bergman from the 1960s to the present day. Bergman is considered something of an outsider artist-photographer; his first exhibition opened in 2009 at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, when he was 65 years old, and he has given only a handful of public interviews since then. The clearest outline of Bergman’s life to date runs as follows: he was born in New Orleans in 1944 to an actress who worked with Le Petit Théâtre du Vieux Carré, a theatre in the French Quarter of New Orleans. His father was a doctor, and died when Bergman was only ten years old. He went on to study philosophy and psychoanalytic theory before dropping out of college (along with his childhood friend, photographer and filmmaker Danny Seymour), before travelling across America to chronicle the faces of his home country.

We might learn most about Bergman by simply looking at his images. They have such a profound presence and such a strong visual identity that I was surprised I hadn’t seen them before, and that Bergman hasn’t received a greater level of international recognition.

Nevertheless, he does not seem to have actively courted fame or notoriety. Rather, his presence as a photographer is as elusive and fringe-like as the people he chooses to photograph. Moreover, perhaps he is not more well known precisely because his images evoke feelings of pain, discomfort and even disgust, and are not always easy to look at. They are similar to Nan Goldin’s work in terms of subject matter, although I would argue Bergman’s aesthetic comes across as more formalist. Bergman has also been compared to Diane Arbus, whose black and white medium format images of society’s outcasts have very much entered the photographic canon. Beyond feeling moved and at times bewildered by the beauty and mystery of his images, after putting the book down, I reflected upon how complex it is to represent issues like homelessness, transitory living, vagrancy and poverty photographically. Bergman’s images made me think specifically about the ethics involved in representing homelessness, as well as how surprisingly interconnected the two are historically.

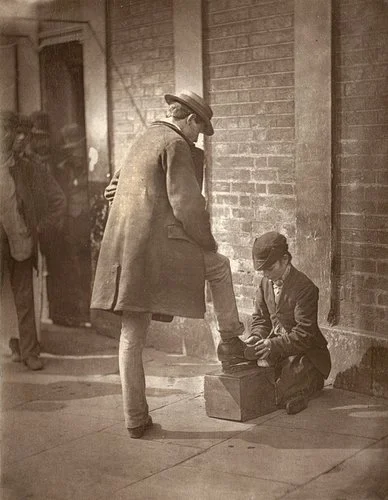

If we look at the first photograph of a human being ever taken, Louis Daguerre’s Boulevard du Temple (1838), it shows someone having their shoes polished on the side of the road. Most distinct is the man extending his leg, but also present, even if it’s only signified by a single black blur, is a second person. This person’s rapid movements are too quick to be properly exposed by Daguerre’s camera; however, they are there in the photograph. Hence, from the infancy of street photography, human beings have been depicted in terms of their class status to one another, and in this iconic image, a higher-class person is rendered visible while the person socially and spatially beneath them becomes invisible. What’s more, the visual ‘solidity’ of the higher status man arises directly because of the street worker, whose labour lasted just long enough for the man above him to stand still and become exposed. While we don’t know who the shoe-shiner is, whether they are an adult or a child, it’s likely they belonged to nineteenth-century Paris’ vast population of itinerant workers, and that they may have been homeless and perhaps even lived on that same corner of the boulevard.

Homeless people have long been easy targets for photographers, and much of the imagery we associate with the Victorian era comes from images of people living in poverty. John Thomson and writer Adolphe Smith produced Street Life in London in 1877, which is considered the first example of social documentary photography. Thomson’s most famous image, The Crawlers, depicts a woman too impoverished to beg. According to Smith's caption, the woman was a widow of a tailor who had fallen into destitution after her son-in-law became unable to work, forcing her to leave her home. She looks after the baby of another woman who has found work, who later paid her in bread and tea. This, at least, is the sanitised description of the woman’s life according to Smith, whose writing was intended to inform, evoke sympathy and hopefully create meaningful social change.

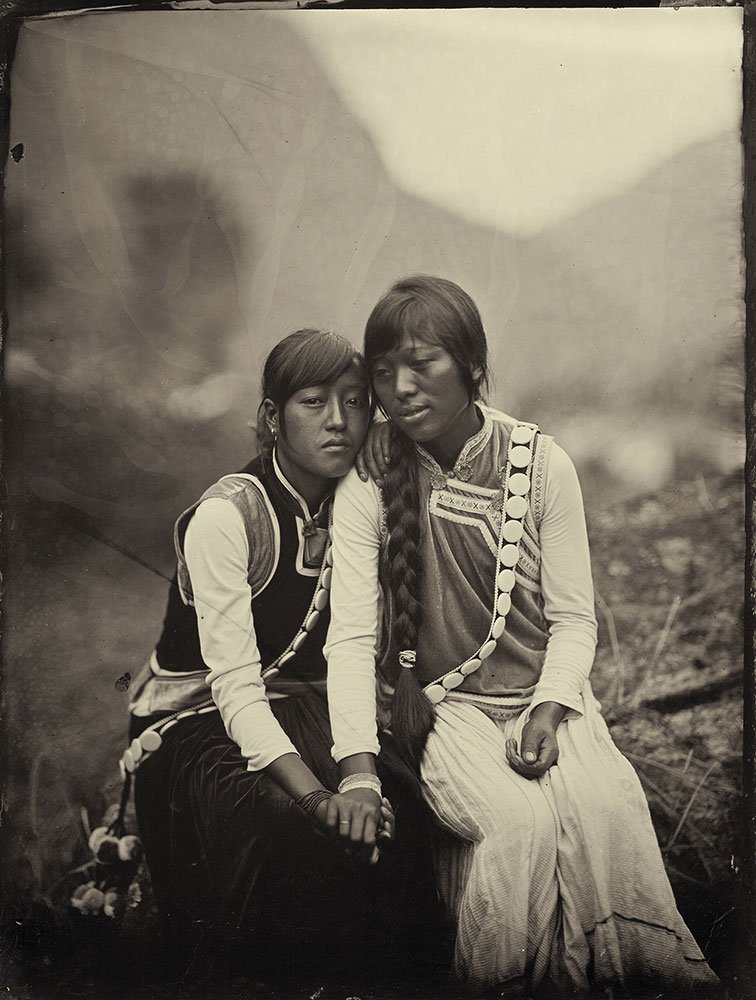

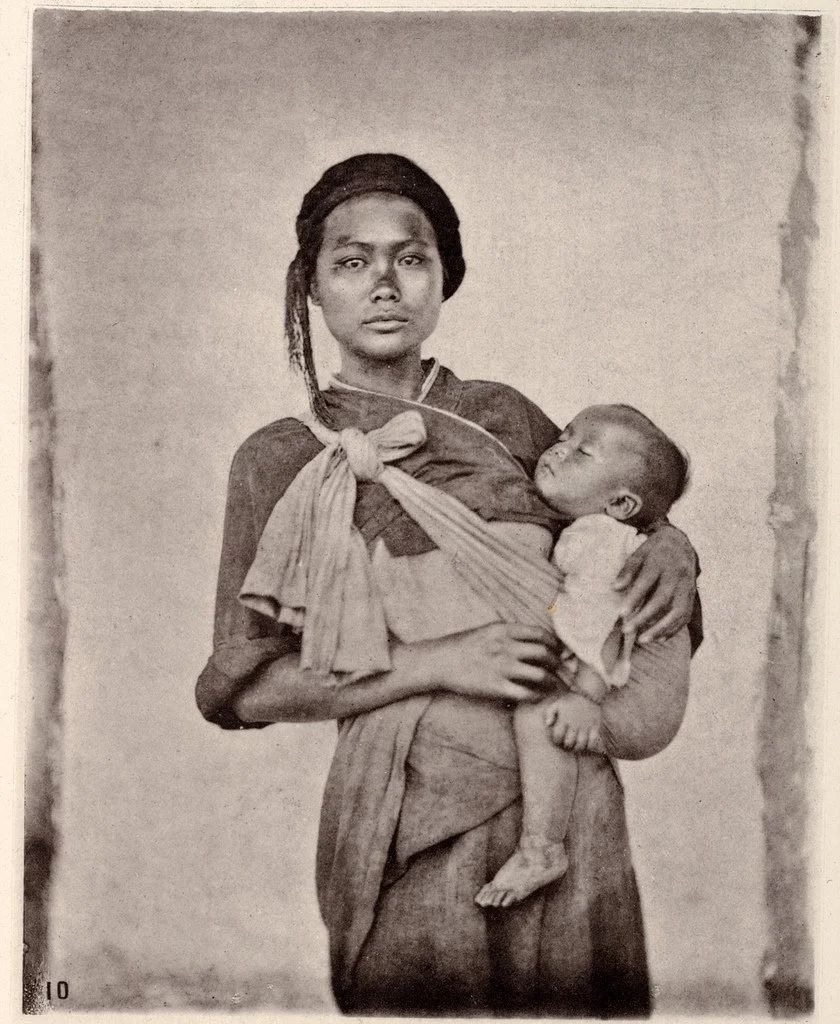

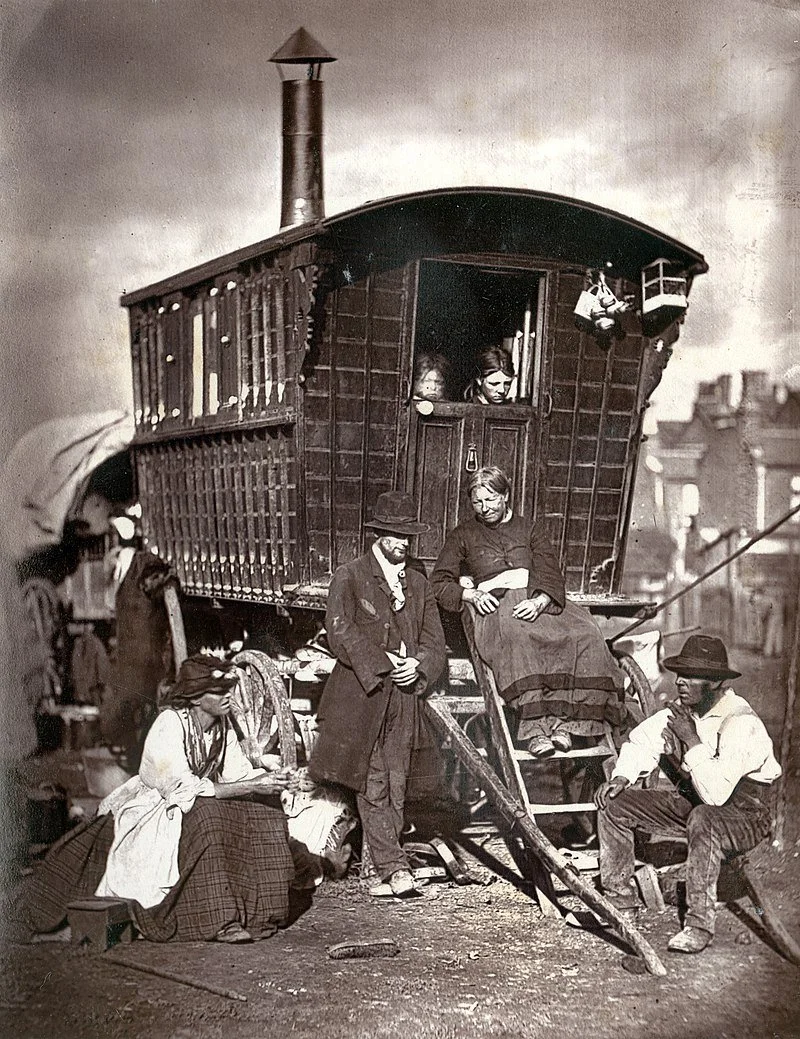

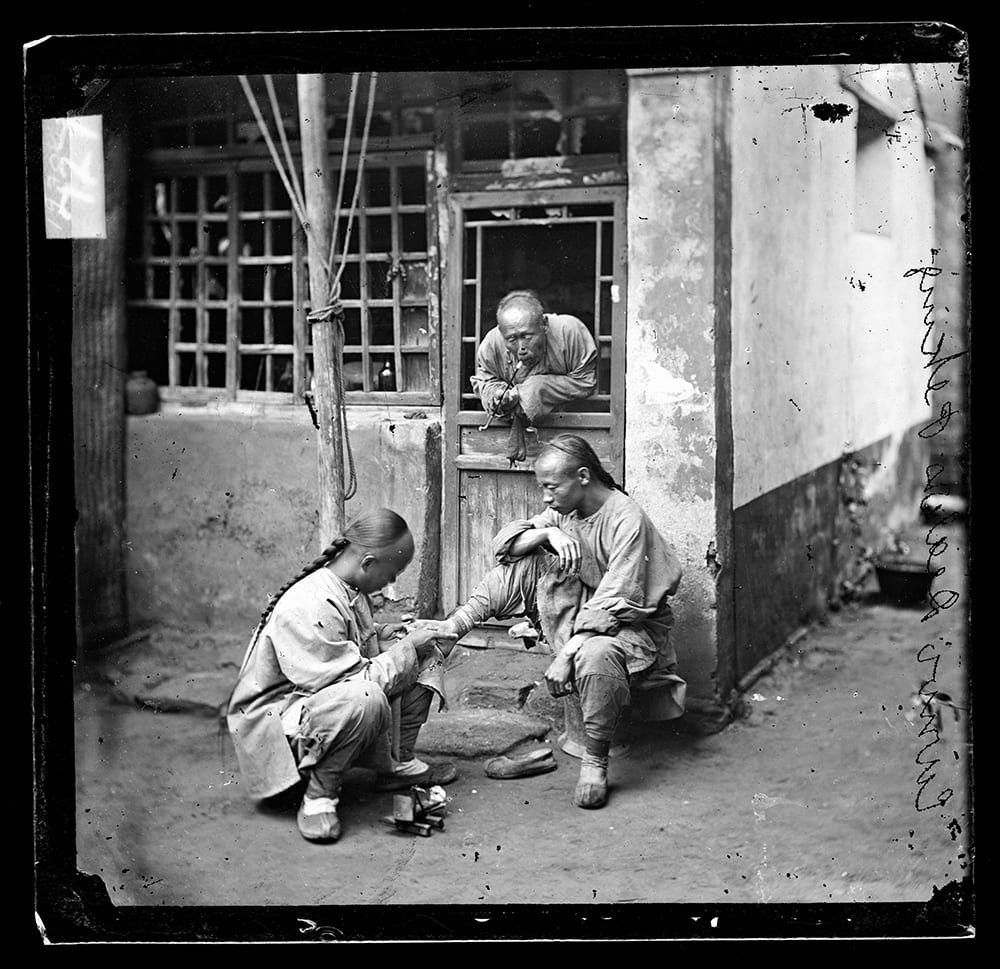

It’s worth noting that John Thomson took his photographs of London’s poor after travelling extensively in East Asia. His portraits of East Asian people are clearly ethnographic, but appear to have been produced with sensitivity and what looks like a certain level of respect for the individuals in front of his lens. By witnessing how people around the world lived, was he able to see more clearly the reality of life back in Britain?

Thomson’s image below, titled The Independent Shoe Black (1877), is fascinating in that the child shoe-shiner becomes the subject of the photographic image for the first time. It is clearly posed, Thomson deliberately pointing the camera so that the face of the child is visible, the impoverished member of society granted a level of respect and even importance above the higher-class man who is presumably paying for his services. Thomson would probably have been aware of Boulevard du Temple as an image, and here he makes corporeal Daguerre’s ghostly street-worker.

While Thomson’s photographs are titled, and a glimpse of their subjects’ life stories is offered in narrative-like detail alongside the images, Bergman’s portraits have no title, caption or location. He deliberately presents us with only the face, and in this sense, recreates the conditions of his photographic encounter with the subject. The critic, John Yau, writes,

“Robert Bergman is a street photographer who doesn’t photograph the street. In this regard, he is on the other end of the spectrum from Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, Gary Winogrand, and William Eggleston. Whereas they locate the figure in a distinct environment, Bergman doesn’t show us much more than the person’s head and shoulders.”

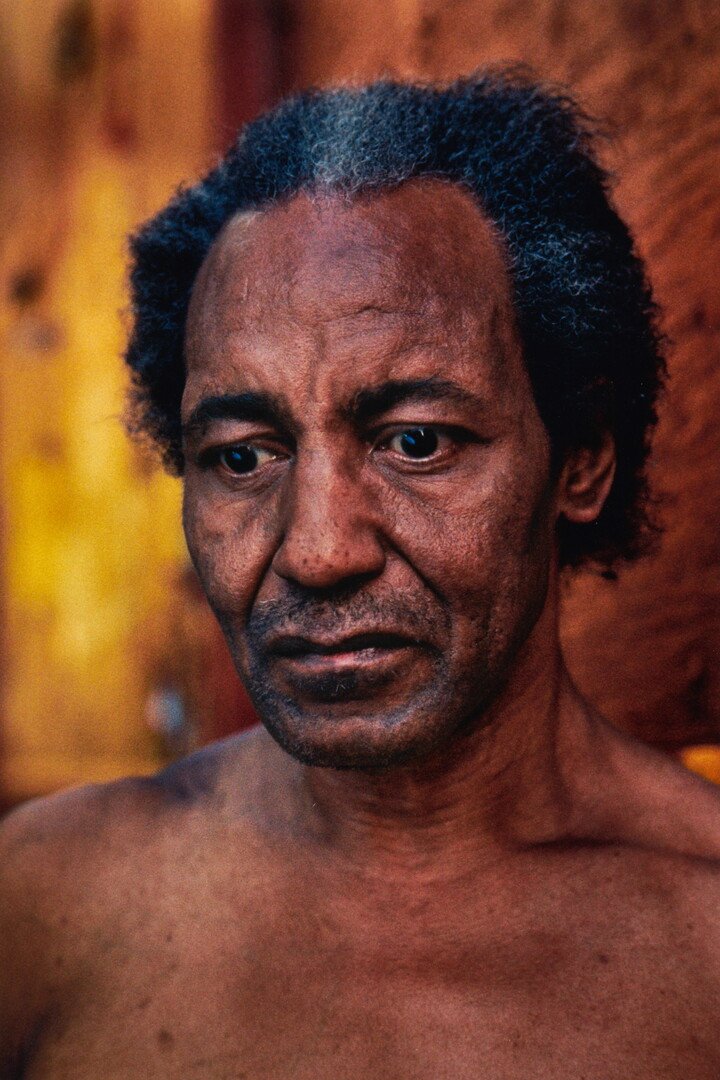

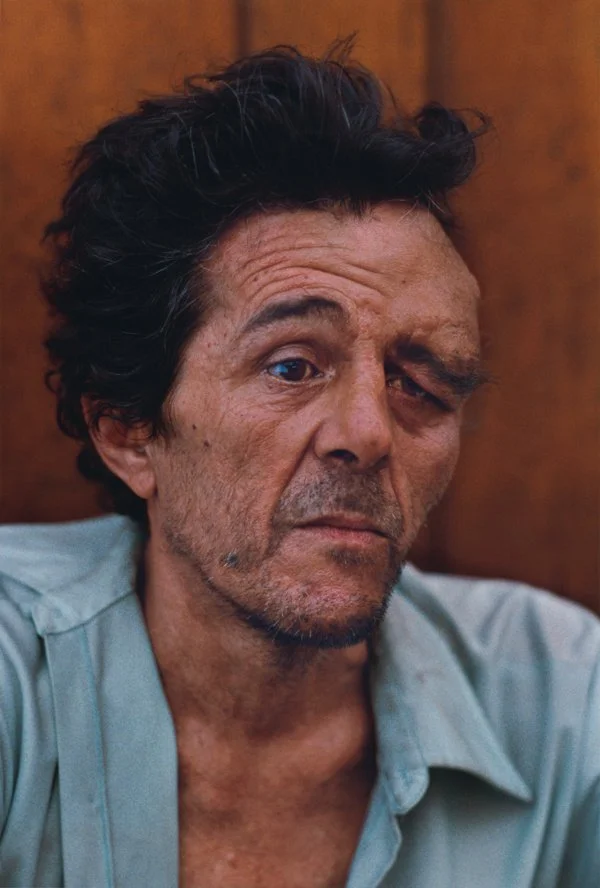

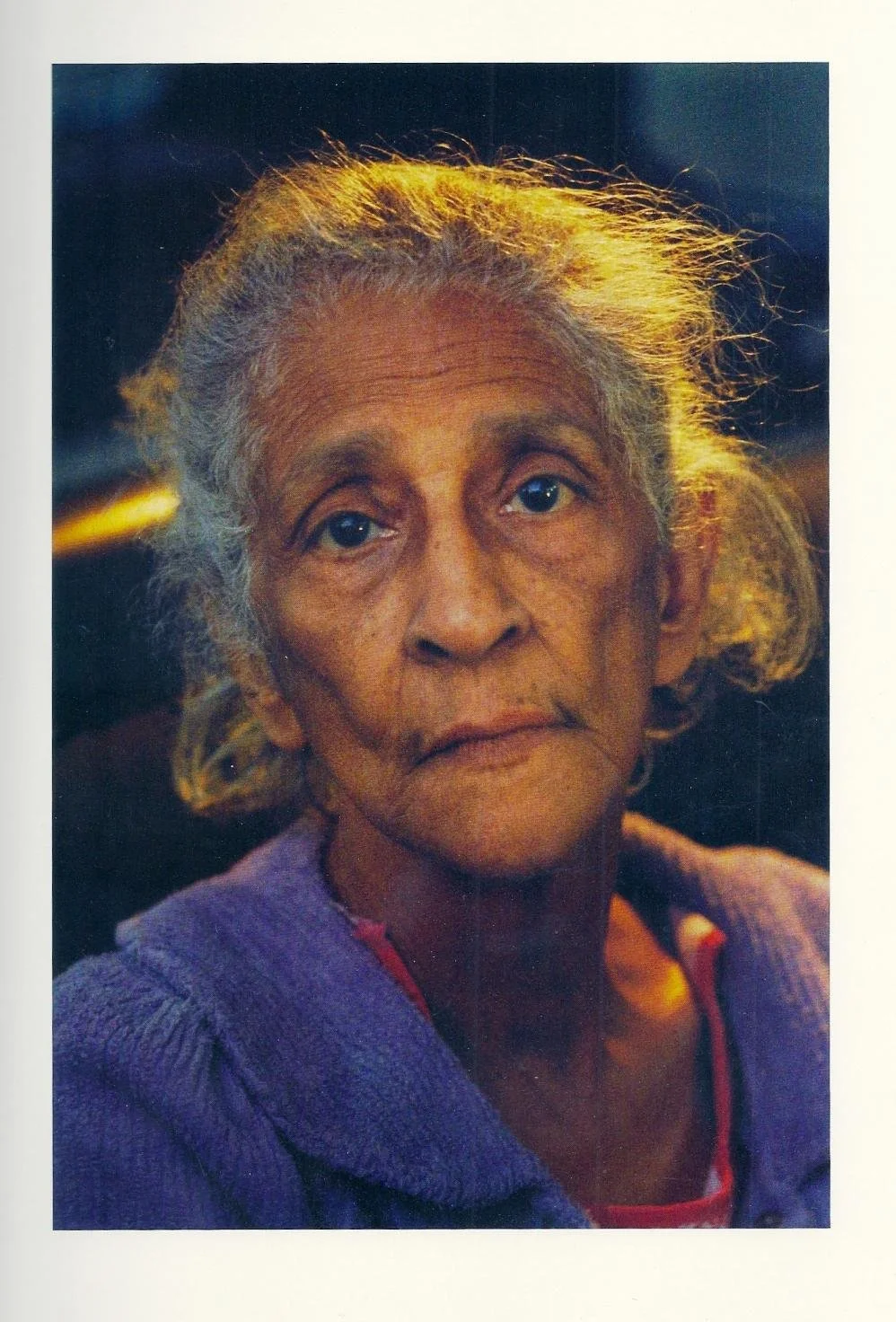

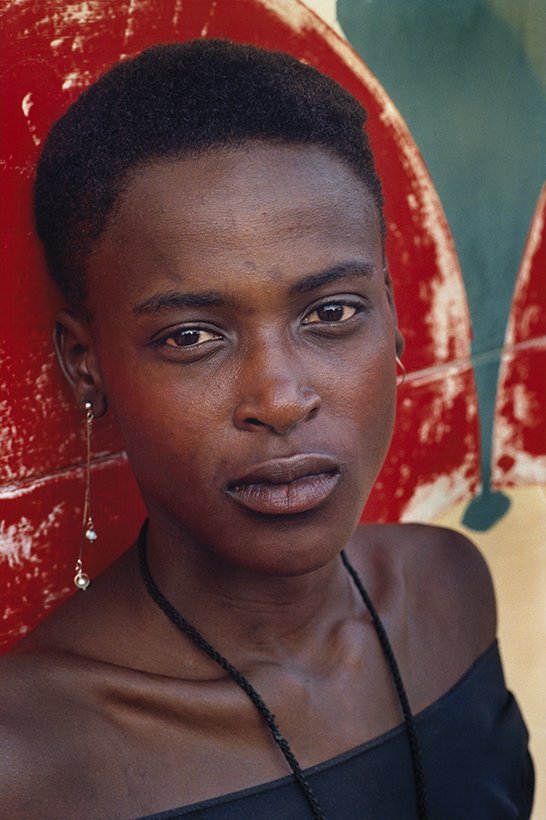

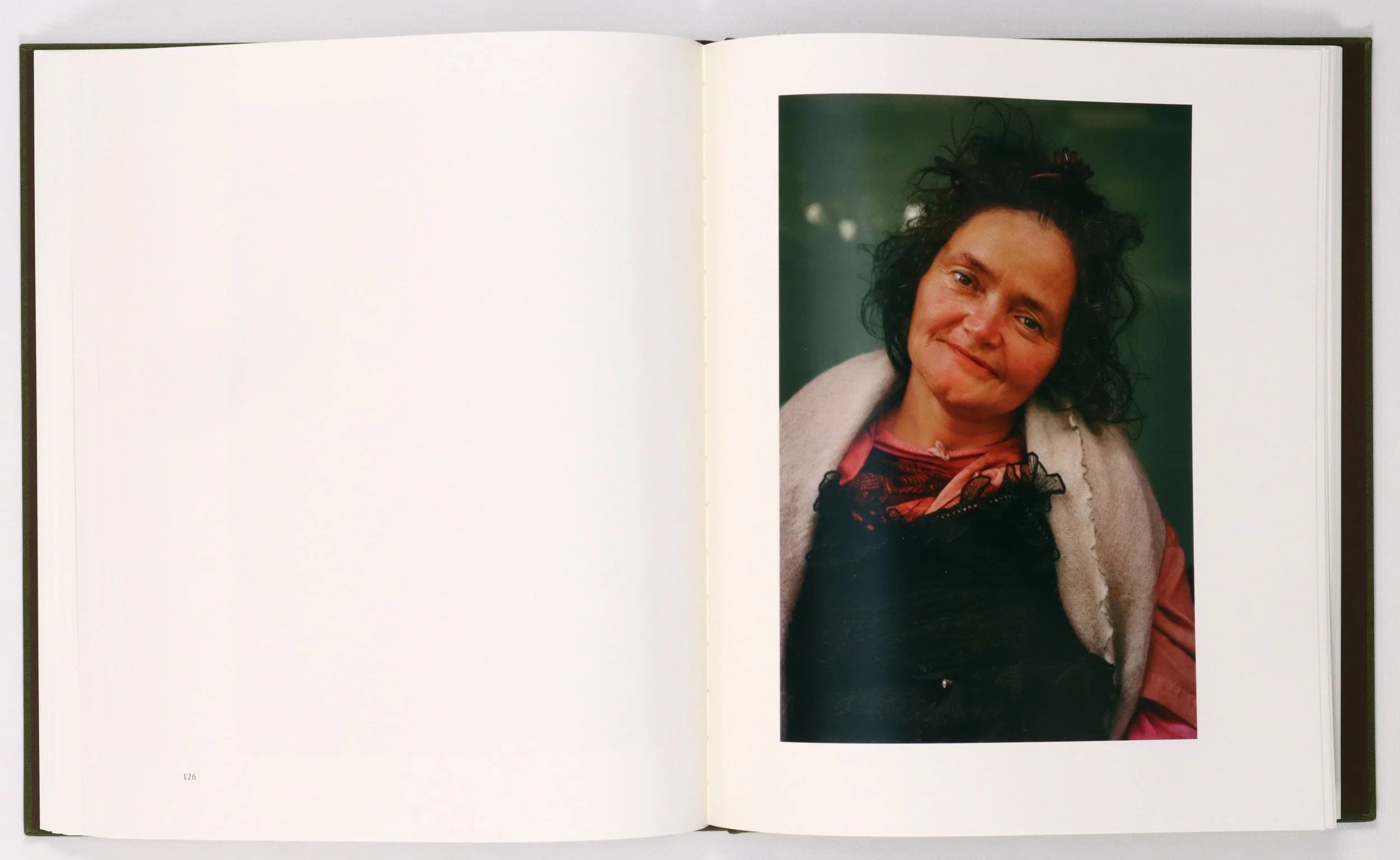

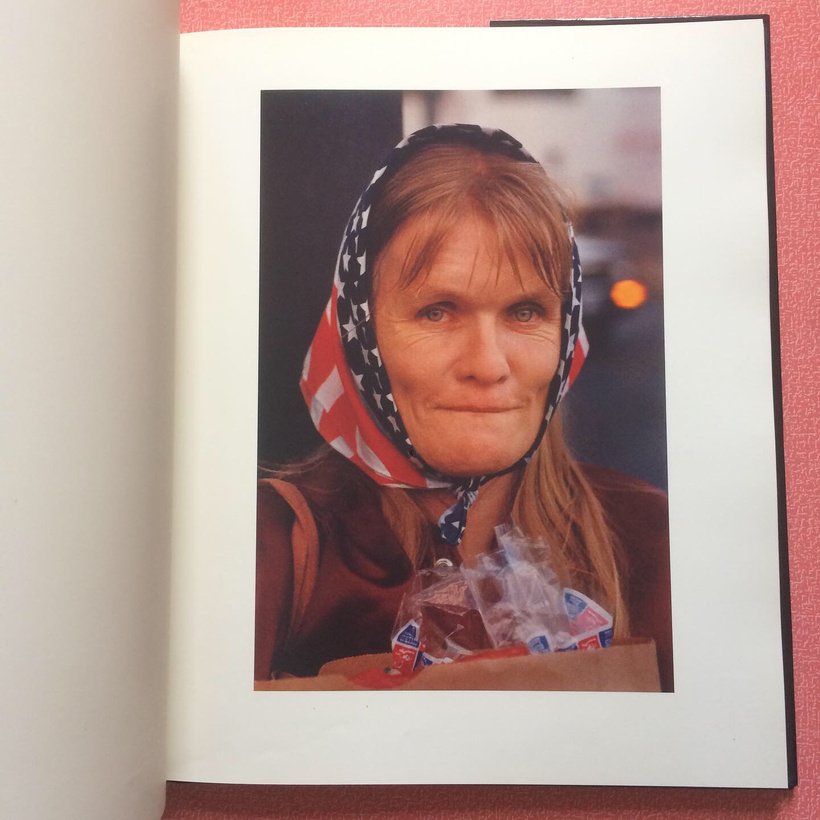

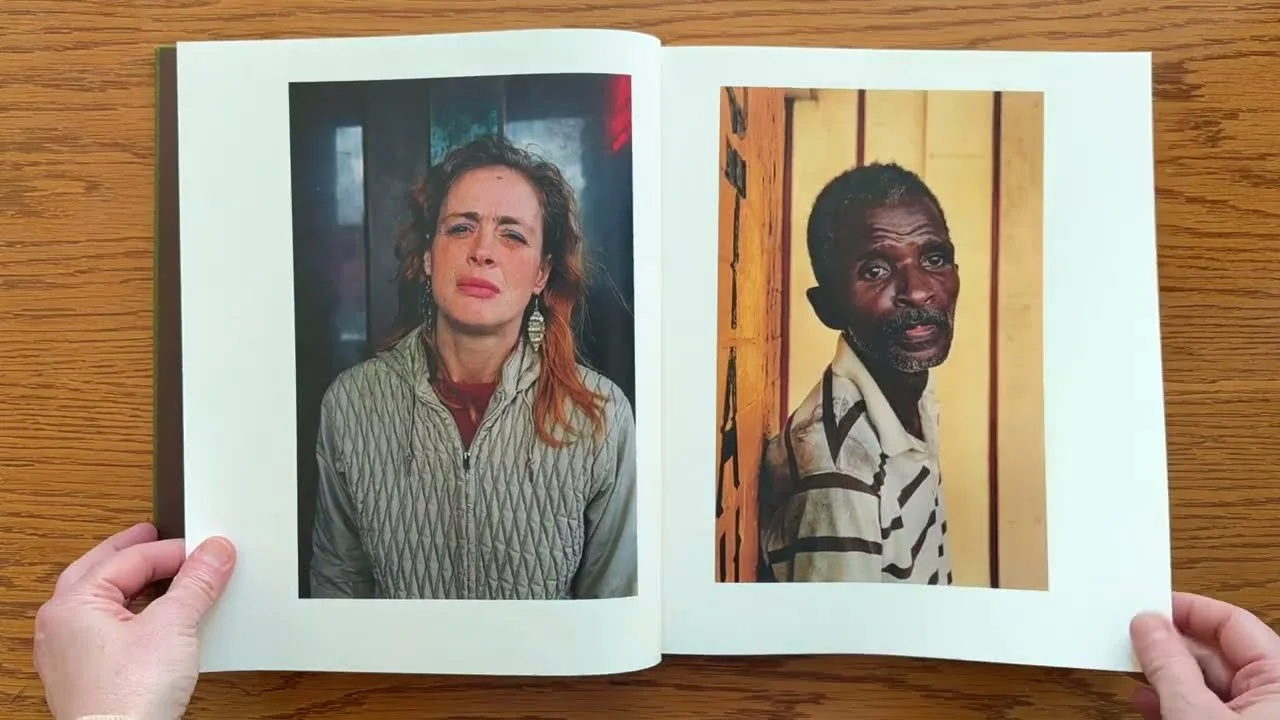

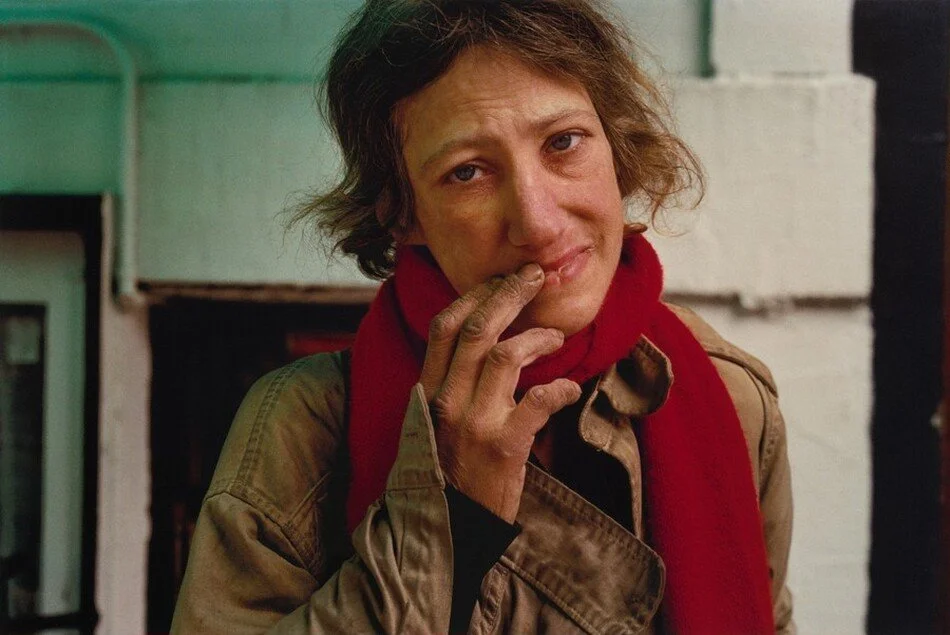

By removing his subjects from their environment, it is arguably a little harder to categorise them neatly into occupation or according to their class status. In fact, in his first publication, A Kind of Rapture, the faces of homeless people coalesce with people who appear to be more financially affluent. By tightly cropping the faces of his subjects and removing them from their environment, he forces us to confront their humanity first and foremost. Page by page, you notice a spectrum of emotional states: reserve, warmth, pride, desperation, yearning, peace and pain float across the different faces. Every image reflects two people (photographer and subject) either finding or attempting to find, moments of intimacy and an almost out-of-the-ordinary level of human connection with each other. A Buddhist monk, after encountering A Kind of Rapture for the first time, contacted Bergman to say, “The effect of looking at the whole book is that you induce the ‘no-mind’ and reveal the Buddha nature better sometimes even than scripture.”

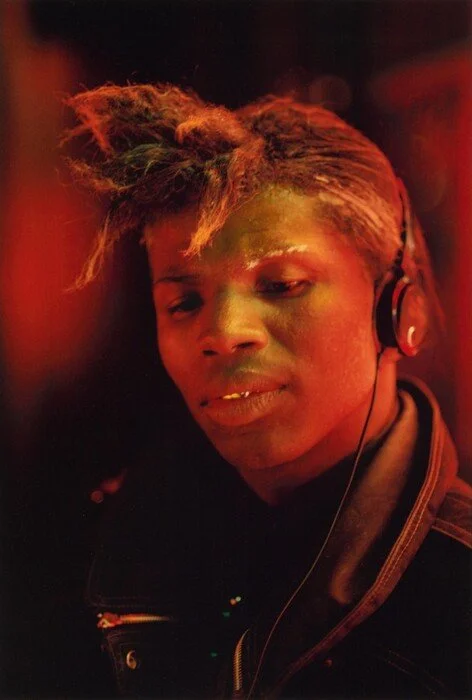

The impact of Bergman’s images rely heavily on the juxtaposition between forlorn facial expressions offset by rich, vibrant background colours. A shirtless man stares pensively at the entrance of an alleyway whose bricks are a blur of gold and burnt crimson, a woman stares impassively into the camera lens, her dress an intense royal purple, the interiors behind her a patchwork of marigold yellows and acid greens, while an elderly man in a bowling hat bites his lower lip, his eyes far far away, the background a tessellation of sap green, violet and deep cornflower blue. The effect is one of sensory overload. His images feel porous. Do we see the world through the eyes of the subject, and is it their sensibility which makes everything so intense and colourful, or does the subject actually affect their environment, colours, as it were, seeping out of them? It almost feels like we are seeing the auras of the subjects, the person photographed intrinsically linked to the colours which surround them. Thinking about the title, Fortune of the Spirit, these colours denote both the ‘fortune’ and ‘spirit’ of the sitters. They are their life experiences manifested into colour, hue and vibrancy belonging to poor people whose lives are rich in experience, feeling and emotion.

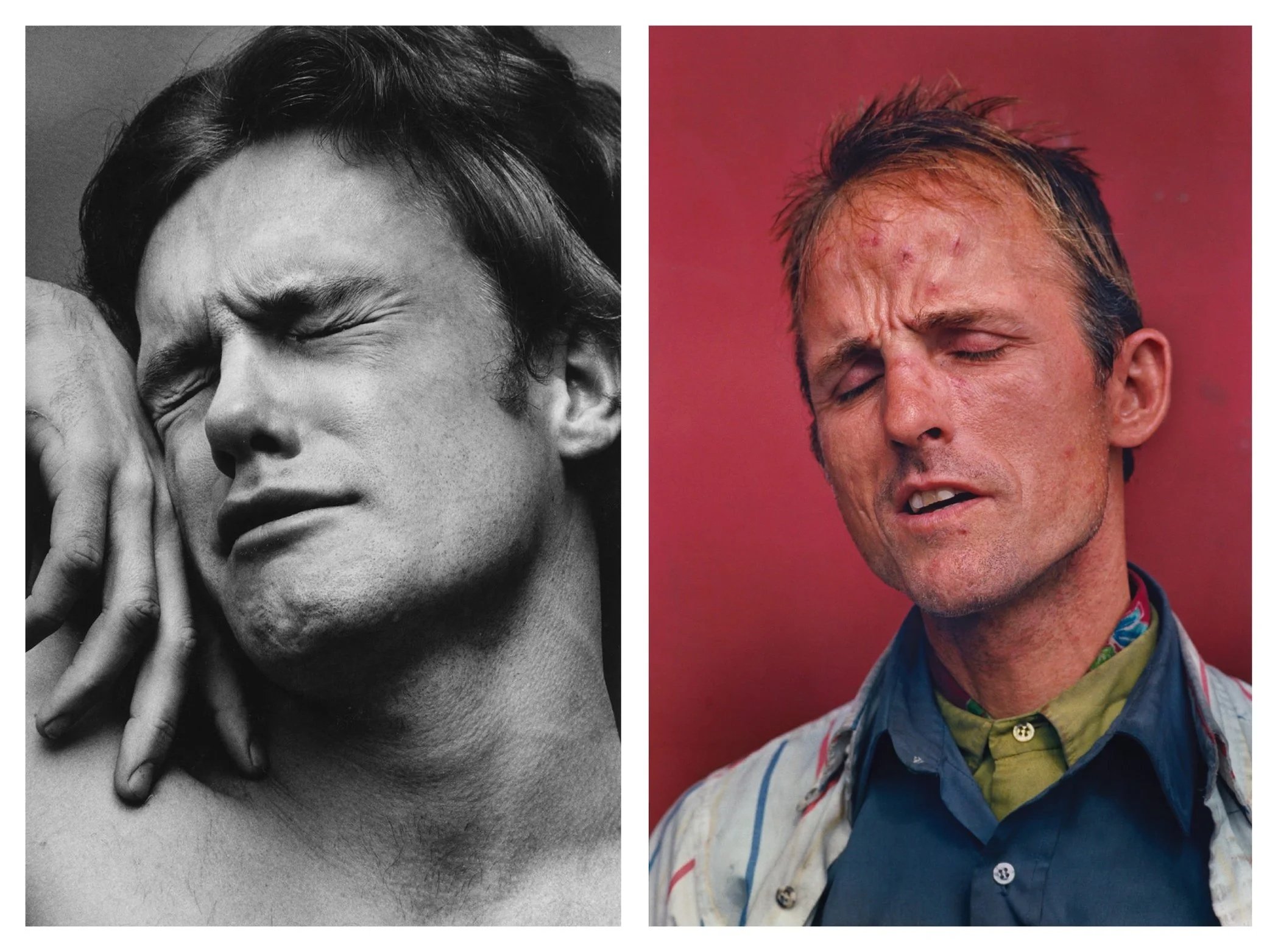

It’s tempting to compare one particular image of a man with his eyes closed to Orgasmic Man (1969) by Peter Hujar, the latter demonstrating the thin line between ecstasy, pleasure and pain. Is the man Bergman has photographed intoxicated, his frown the result of pleasure and a release from the here and now? Is he simply captured halfway through talking, or even singing, and have I projected the idea of intoxication onto him because of his closed eyes and dishevelled appearance? Or is the man overcome with emotion and on the edge of tears? For me, the image speaks hugely of transcience. He looks physically unwell and positioned on a threshold somewhere between life and death, meaning the in-between nature of his expression makes his overall demeanour all the more transitional and precarious.

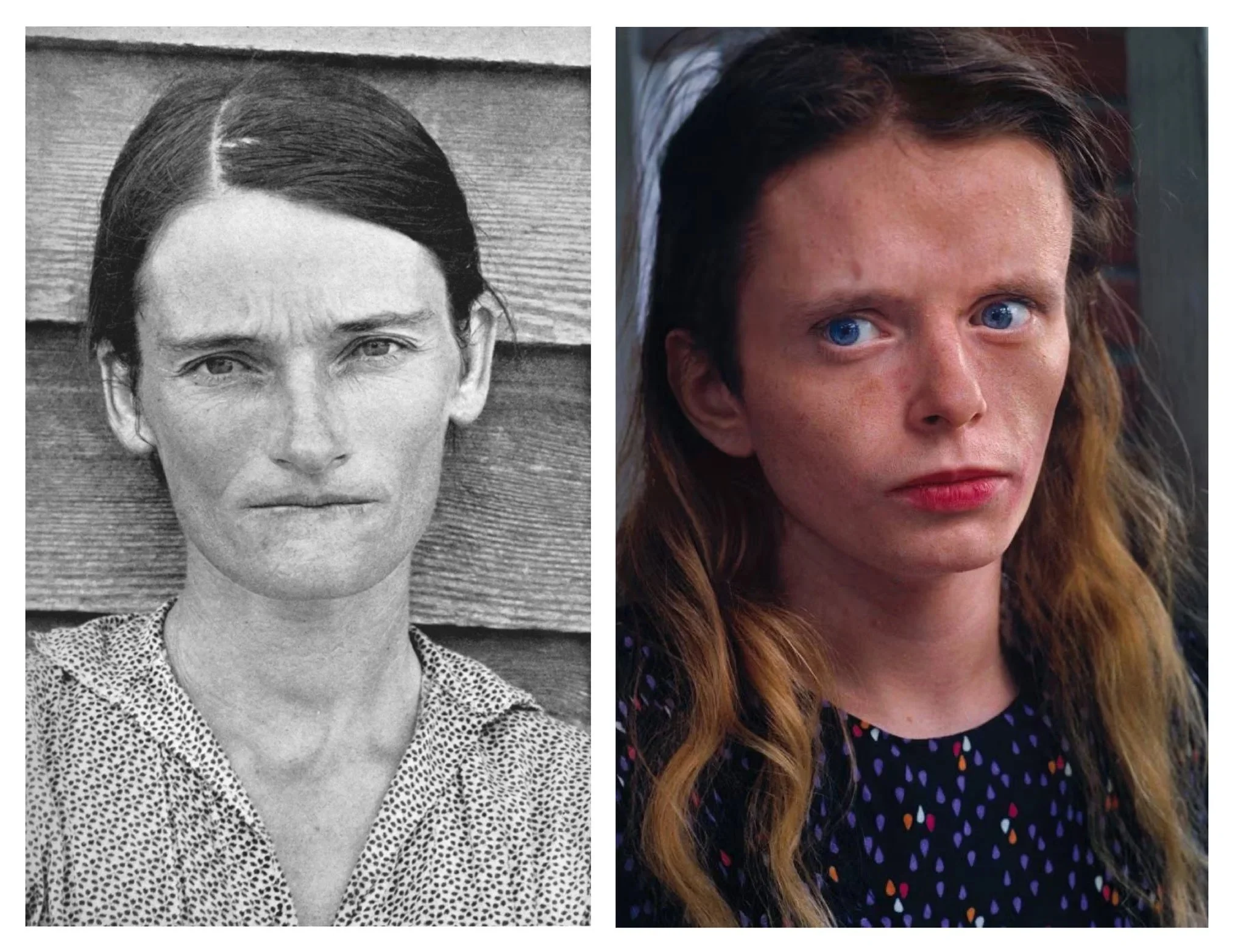

Another of Bergman’s portraits of a young woman recalls a woman in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, by James Agee and Walker Evans. Agee and Evans captioned the portrait Annie Mae (Woods) Gudger in order to protect the identity of the real-life subject, Allie Mae Burroughs. While Gudger/Burroughs' portrait is less well known than, say, Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936), both images have become synonymous with the Great Depression of the Deep South. Even if the similarities are unintentional, when viewed side by side, Bergman’s portrait reminds us that the American Dream is not possible for all and that poverty, unfortunately, remains timeless in the context of both American and human history. The faint smear of red lipstick beside the young woman’s mouth opens up additional layers of narrative and interpretation.

Left: Annie Mae (Woods) Gudger (1941) by Walker Evans

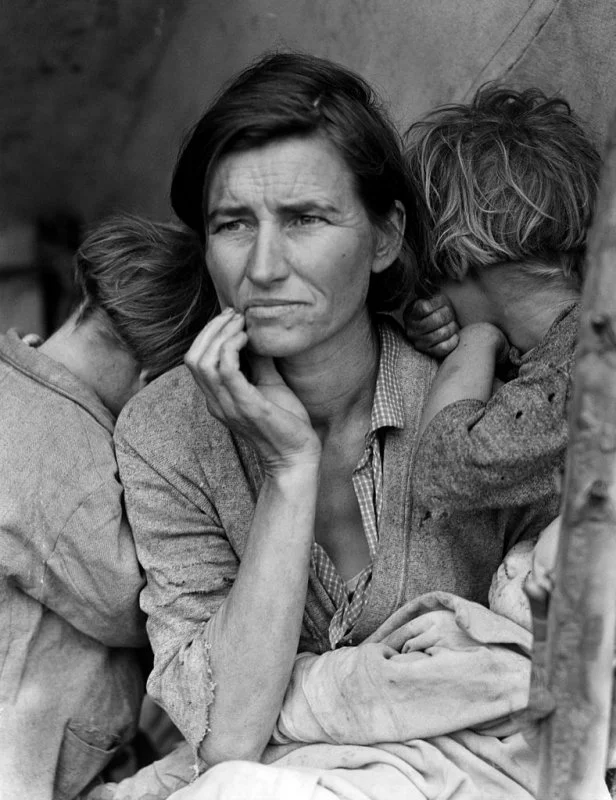

Migrant Mother (1936) by Dorothea Lange

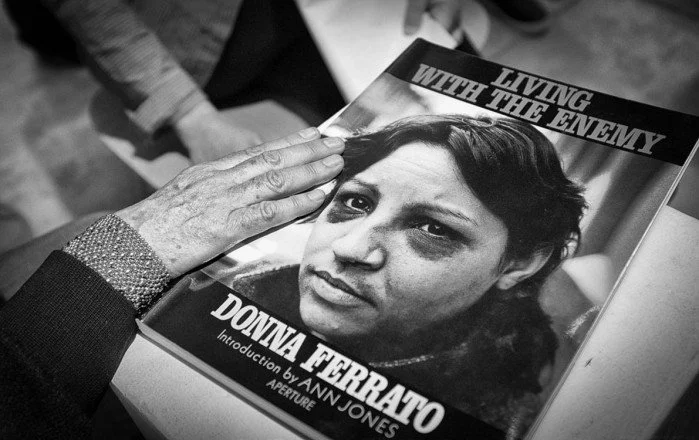

Perhaps it’s no surprise Bergman isn’t more well-known, as there is arguably something unfashionable about his style. Not titling his work or offering further context about the lives of his subjects could speak of a distance between photographer and subject that is sometimes frowned upon by contemporary curators and scholars. His approach feels different to, say, photojournalist Donna Ferrato, who actually lived with (for months and sometimes years at a time) the people she photographed. In Living with the Enemy, Ferrato documents women and children experiencing the trauma of domestic violence within their own homes. Ferrato’s landmark images were integral to making visible an issue that affected a vast amount of the American population, and her images contributed to a shift in how society, media and law makers viewed intimate-partner abuse. Bergman photographs people who likewise appear to have experienced extreme suffering, yet they feel less overtly political. Then again, details in his portraits do allude to the HIV/AIDS Epidemic, like the red AIDS awareness ribbon pinned to a young woman’s denim jacket. His photographs were mainly taken in the 1980s and early 1990s, years in which HIV/AIDS profoundly affected American life, particularly in urban communities. While the mood of loss resonates in his images, the lack of context around his portraits invites viewers to consider the lives and struggles of the people depicted without defining them solely by illness.

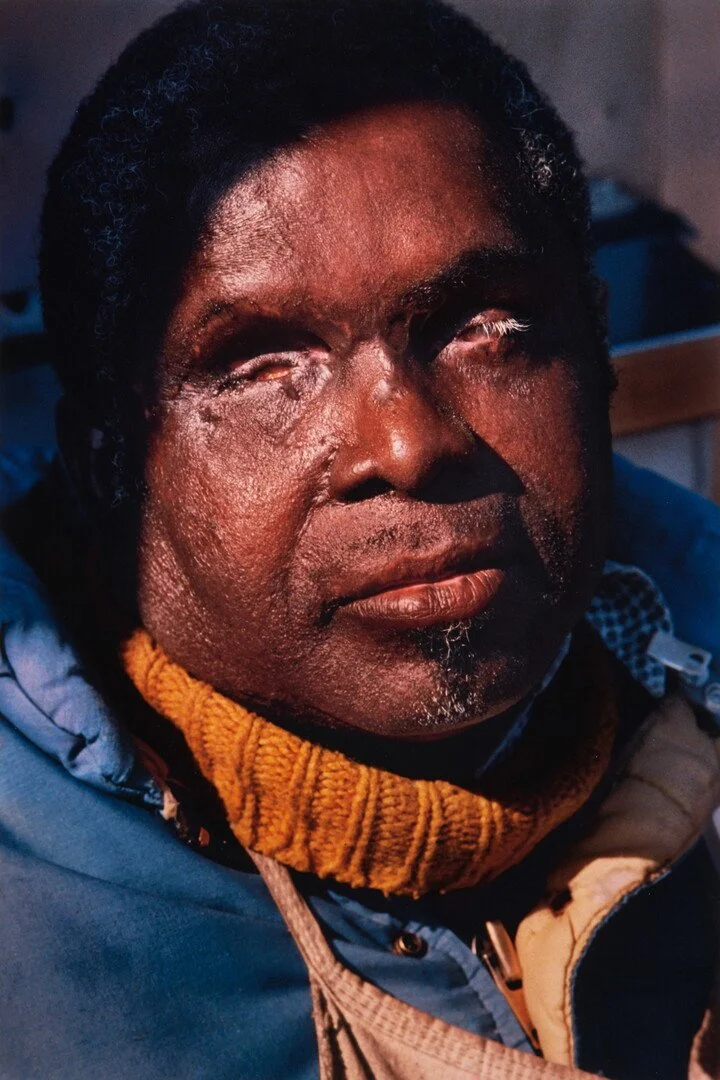

Bergman’s approach also feels different to someone like Boris Mikhailov, whose Case History (1997-1998) documents people in Kharkiv, Ukraine, whose homelessness was partly a consequence of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Although ethically complex, Mikhailov would pay his subjects for modelling for him, either with money, food or alcohol (depending on what people asked for). Both Mikhailov and Bergman have a tendency to draw upon Christian iconography when photographing their subjects. Mikhailov created pietà-like tableaux to frame marginalised people within the same visual categories typically reserved for “heroic” or “sacred” figures. Bergman’s figures, placed in front of highly saturated backgrounds, likewise resemble Christian icons. In the image below, I can’t help but see the sign behind the man as a sort of halo.

From Case History (1997–1998) by Boris Mikhailov

Untitled by Robert Bergman

Sometimes, the more we know someone, the more we shape-shift to meet their expectations. We seek to impress, to persuade, seduce, soften edges and obscure flaws and end up performing versions of ourselves so as to become palatable to the other person. Bergman, by contrast, photographs the very first encounter, before any of those negotiations have taken place. In doing so, he manages to bypass the layers of artifice we accumulate and, I would argue, unearths the kernel of who people really are. The Art Historian, Meyer Schapiro, observed:

“Robert Bergman’s colour portraits of people encountered by chance on the streets of American cities address the viewer with captivating simplicity and directness…the resulting energy and beauty of forms imbue these portraits with unnameable yet compelling spiritual qualities.”

Ultimately, what unites Bergman’s portraits is their underlying sense of compassion. Even when the sitter looks away or deliberately avoids the camera’s eye, you sense Bergman’s curiosity, care and respect emanating toward them through the view-finder and through the camera lens. Art Critic, David Levi Strauss, in “The Democracy of Universal Vulnerability: On Robert Bergman's Portraits”, argues that humanity has always pivoted between extremes of cruelty and kindness:

“We injure, torture, terrorize and enslave each other on a massive scale…because we have discerned some difference in the other that we imagine overrules our common humanity...Each new generation of image-makers finds fresh ways to make human cruelty visible.”

Many of Bergman’s subjects bear traces of this suffering and cruelty, be it emotional, economic or existential, yet crucially his images refuse to reduce them purely to that suffering. Rather, Bergman makes visible the fact that, irrespective of class and economic differences, we are all equally human, equally alive, and, given the right circumstances, we have the capacity to open ourselves up to each other in moments of emotional contact. His portraits remind us that our deepest point of connection is simply to encounter one another, to truly look at each other and to share ourselves in moments of vulnerability and trust.