Part of the reason I love photography is that it recreates some of the conditions of theatre. If the person in front of the camera lens knows they are being photographed, chances are they will end up performing in some way, even if their pose says “I’m going to nonchalantly pretend the camera isn’t there!” How someone changes their facial expressions, adjusts their stance or directs their gaze towards or away from the camera speaks volumes. It indicates how they see themselves from the inside and how they would like to be viewed from the outside. We might even channel, albeit unconsciously, the poses we’ve seen adopted by people in magazines, paintings, television shows or movies. Hence one pose can hold a plethora of performances within it – what is photographed becoming an echo of an echo, as it were. Sometimes someone might try to give the camera a particular expression, but when the photograph is developed a different one entirely appears, despite their best efforts to conceal it. More interesting still is the process of photographing a professional performer who manages to channel the essence of an imaginary character at the same time as revealing the truth of who they are as an individual. Ultimately, every photograph represents a collaboration of sorts, the photographer focusing on someone or something and seeking to bring it into a relationship with its surroundings. We can’t help but project a narrative onto an image, the photograph becoming like a play in frozen miniature, its square or rectangular shape echoing the lines of a stage.

The Dutch photographer, Scarlett Hooft Graafland (b. 1973) creates images which share the qualities of theatre and live performance. Her arresting images transport you to far-flung landscapes which act as colossal stages where solitary individuals or Greek-style choruses take centre stage, their presence sometimes purposeful and bold, at other times absurd and non-linear. In 2016, she told Unseen Magazine

“[My photographic work]…does indeed have some relation to performance art and to sculpture, although these performances are undertaken in isolated locations without any audience to witness them. The only thing that remains of them is the photograph. Photography is a medium that is associated with the representation of truth, and in my work I use it to represent the fantastic and the irrational. I like to work with surreal imagery because I like the ambiguity of it…The vast, surreal landscapes in my photographs become the chorus of a classical tragicomedy that silently comments on the subject.

Still Life with Camel, 2016

Still Life with Camel is one of Hooft Graafland’s most defining images. Like many of her works, it features figures ambiguously placed within a large, dominating landscape. She has stated, “In the Netherlands, we are used to man-made landscapes, which might make us think that we are superior to our surroundings and that we can design the whole world according to our own wishes”. The desert certainly looks wild, but with its carefully arranged figures and precise composition, the image also has the air of having been carefully designed or staged by the photographer. Thinking about sculpture, the epic scale of the desert and the way the cloth drapes so dramatically over the figures reminds me of the land art of Christo and Jeanne-Claude:

Dunes Like You, 2016

In Western Media, the Middle East is often depicted as a land of danger, conflict and religious extremism. Still Life with Camel and Dunes Like You subvert our expectations of the Muslim world, the bubble-gum pink of the fabric giving the figures a playful, perhaps even effeminate energy, making us question the identities of the figures beneath. I love the way the camera is positioned above the eye-line of the figures as if the viewer is hovering in the air or rising up above the sand. You feel like a fly, not on the wall, but in the air, privy to some covert ritual or dance whose purpose is unclear. These images also remind me of the Taliban series attributed to Thomas Dworzak, which show passport photos of members of the Taliban retouched with brightly coloured halos and flowers, and which offer an entirely different view of Afghanistan’s terrorist military group.

Hooft Graafland’s work features people and places one could easily term “exotic” and taken at face value her practice parallels the journeys taken by European explorers of bygone centuries, who sought to study new worlds from an anthropological (and colonial) point of view. On one level she doesn’t shy away from these potentially uncomfortable parallels, the title of her 2017 exhibition, Discovery, possibly alluding to the ‘Age of Discovery’ of the 15th – 17th centuries.

Resolution, 2015

Resolution is an incredible image, taken on Malekula Island in Vanuatu in the Pacific Ocean. This boy is a descendant of the chief of the tribe that welcomed Captain Cook to the island two and a half centuries ago when Cook’s ship anchored at the same spot.

Despite the stillness of the water, the image feels highly charged, the boy turned away from the camera as if ignoring the photographer’s presence, and at the same time confronting the model of the HMS Resolution which represents his island’s colonial past, the yellow of the ship the same yellow as his modern Adidas shorts. The image asks more questions than it answers, and to my eyes seems to meditate on the past, present and even future. It is both staged and very much real, a microcosm of forces much larger than itself.

Hooft Graafland stays in specific locations for extended periods of time, meaning each project becomes a collaboration with the local people, who share local knowledge, participate in the process of production and perform for the camera. Many images depict local customs, with rituals, folk-lore and mythologies re-interpreted and re-imagined in relation to the landscape. It’s often unclear as to what local issue or mythology is being explored, but this only adds to the image’s mystique. In a sense we feel all the more distanced from the scene, yet because of its strangeness, we try and make sense of it and thus become complicit with it. We don’t know why these Muslim women are carrying balloons, so in all likelihood we invent a reason in our heads, symbolically joining them as they walk along the beach.

Burka Balloons, 2014

Hooft Graafland’s subjects often hold objects that are either symbolic of their culture or which are artificial and out-of-place with their surroundings. Hence her work shares the qualities of Surrealist painting, and can be compared to the work of German theatre practitioner, Bertolt Brecht, who developed the ‘Verfremdungseffekt’ or ‘distancing effect’. Brecht encouraged his performers to move away from naturalistic acting and to dress and handle props in such a way which shattered the illusion of reality. This “making strange” then forced the audience to re-experience the world around them as if for the first time. Hooft Graafland is likewise interested in seeing things with fresh eyes: “On arrival in unfamiliar and often mysterious surroundings, I experience something that I would like to call the “hyperreal”. This “hyperreal” experience relates to an intensified vision of reality that transcends the ordinary.”

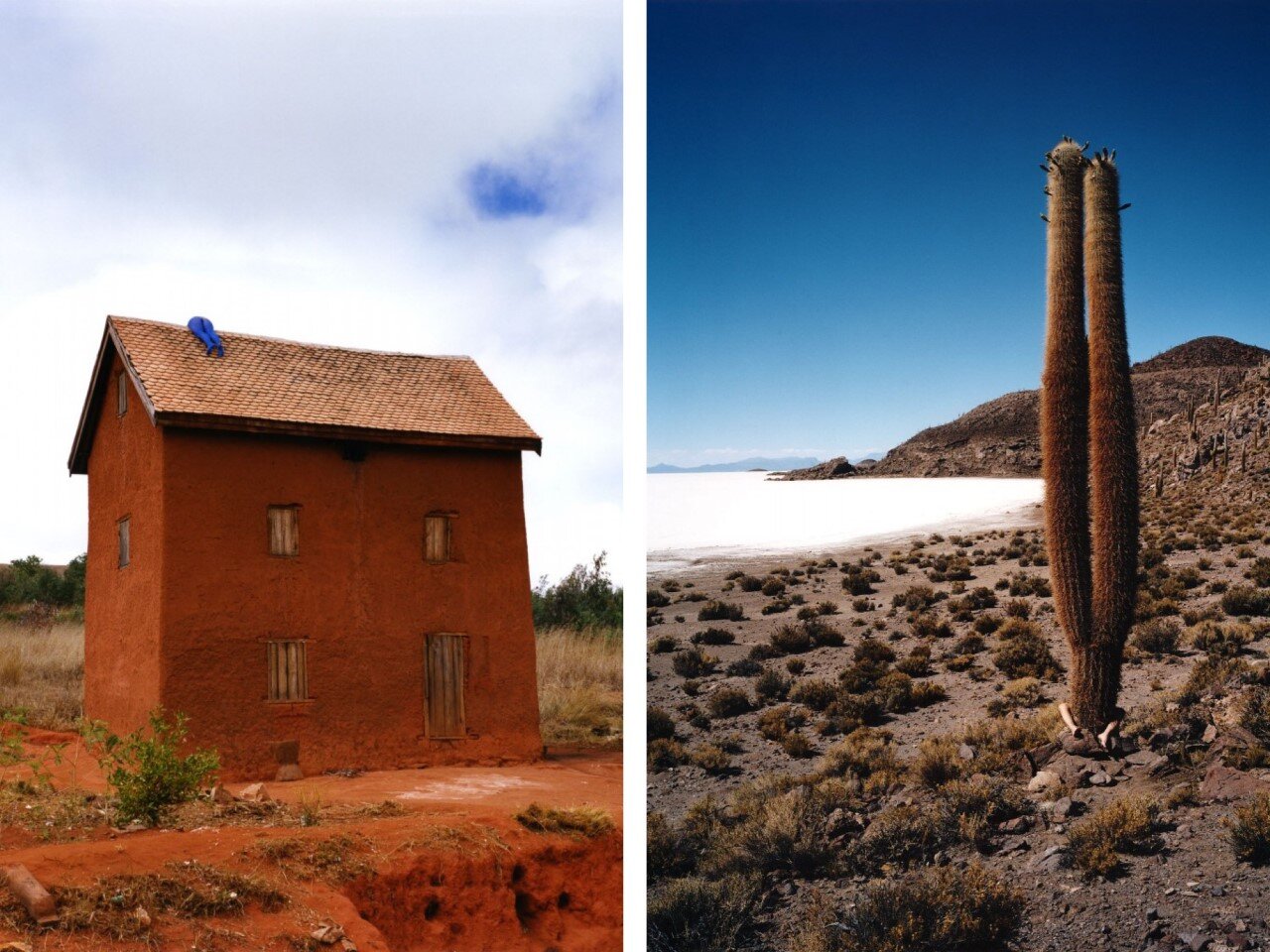

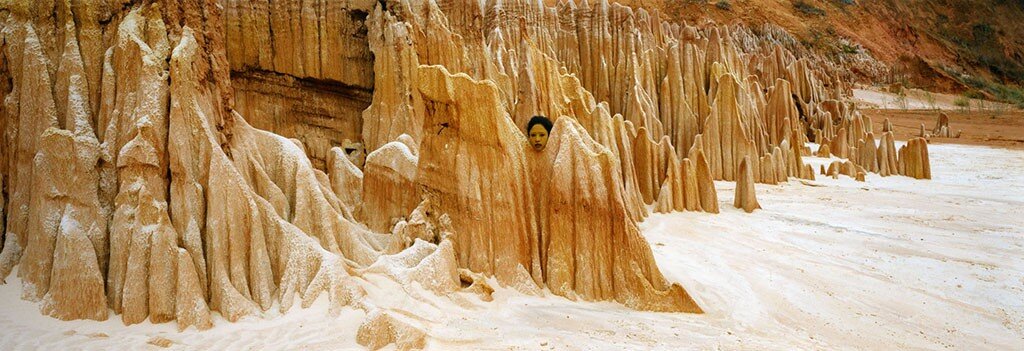

Red House, 2013 Discovery, 2006

It’s worth noting Hooft Graafland also places herself in front of the camera, creating images where her body (often naked or painted blue) performs in relation to a landscape. In Bolivia, her legs wrap suggestively around a cactus tree, whilst in Madagascar, like a cartoon Eve flicked out of the garden of Eden by the giant fingers of God, her naked lower body is splayed out comically on the roof of a house. There is something comedic in the way her limbs only become visible upon closer inspection as if she is trying and failing to hide her presence from the camera. Her nakedness also encourages us to identify with her – we’re all born naked after all. By looking at these images, we experience a re-birth of sorts which matches the “hyper-real intensified vision of reality” Hooft Graafland describes upon first experiencing the extremity of a new landscape. You can’t look at her images without appreciating on a visceral level the spikiness, hardness, dryness, softness and vastness of the world we all belong to. In this sense, her images have something in common with Ryan McGinley’s breathtaking photographs of nymph-like bodies that swing from branches, leap into waterfalls and drift through caves, at one with nature.

What comes across most strongly in Hooft Graafland’s work is her mixture of reverence and irreverence for landscapes and the people who inhabit them. In the art world, work featuring or co-created by indigenous communities and people who live beyond the developed world is often treated in rather serious terms or venerated for its perceived authenticity and truth. It’s interesting to see people from remote corners of the world either expressing themselves or being depicted in playful, experimental and (to use a European phrase) “avant-garde” terms.

Encountering different cultures is obviously a two-sided affair. Hooft Graafland states “In the wilderness, I become conscious of being alive; and in foreign cultures, I’m made aware of my own identity. This sense of liberation often contrasts with the traditions of the local culture. When entering and living in an unfamiliar culture for the first time, its compulsory behaviours and restraints can be felt.”

The idea of ‘compulsory behaviours’ is perhaps key to making sense of Hooft Graafland’s work. Her photographs show people engaging in play, both escaping societal norms and demonstrating these norms needn’t be set in stone. Rather, new ways of being are created and captured on film; poses and configurations which adhere to their own logic. The local people who occupy their remote landscapes can be as surreal, free, expressive, abstract and undefined as the landscapes they find themselves in. The way I see it, Hooft Graafland’s landscapes are empty stages which host an assortment of different actors, whose presence tells a story which transcends easy definition and which has the power to shift depending on the eyes of its audience.

Moonlight Renala, 2019

Sons of the Forest, 2015

Salt Steps, 2004

Taken on the salt flats of Bolivia: “One of the most popular cartoons in that region is the Hulk, about an ordinary man, who, if angry, gets inflated and transforms into a powerful giant.”

Out of Continuum, 2007

Six Bowlers, 2015

Balancing Bamboo 3, 2015

Fish, 2012

Angèle, 2012-13

Blues, 2013

Hut, 2012-13